Last week on

Wandering DMs we had a smashing chat with one of our favorite repeat guests, Matt Finch of Mythmere Games. As I write this, his Kickstarter for the new

Swords & Wizards Complete Revised edition is entering its last few days -- you should check it out if you can.

Matt is both epically knowledgeable about old-school D&D, and also impressively generous with his time and wisdom. After the live show he hung out for another hour to chat with he patrons on our Discord server (accessible at any tier on our Patreon). As part of that discussion, we got on the subject of Carrion Crawlers. Almost everyone involved had a different take on some part of how they should work -- and as we dug out our various books, it turns out that every one of our competing interpretations had some support from one text or another, which was entirely fascinating.

The Carrion Crawler is rather infamous for being probably the most brokenly imbalanced creature in early D&D. Positioned as a 2nd level monster on its birth in OD&D (Supplement I), it was re-evaluated as 6th level in the AD&D DMG, and got a special badge in its Monster Manual text: "... these monsters are greatly feared". Don Turnbull's MonsterMark System from the White Dwarf has an especially problematic time handling it. Frank Mentzer put forward using one as the single biggest mistake of his DM'ing career. And on and on. But what makes it the flagship for busting up a DM's best-laid plans?

OD&D Greyhawk (1976)

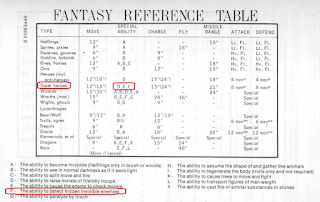

CARRION CRAWLERS: These scavangers will usually attack in order to insure that there will continue to be a supply of corpses to scavenge. They are worm-shaped, about 9’ in length, 3’ high at their head end, and move quickly on multiple legs. Their mouths are surrounded by eight tentacles of about 2’ length, and their touch causes paralization (save vs. or paralized). The Carrion Crawler is able to climb/move along walls or ceilings as readily as floors, thus allowing it to compete with Ochre Jellies, Black (or Gray) Puddings, and the like.

The "Attacks and Damage by Monster Type" table in this book (p. 16-19) confirms that a carrion crawler gets "8 tentacles" for its number of attacks, which is a very large number (rivaled only by octopi, squids, and hydra). The damage entry just says, "special", and the text here notes the paralyzing attack, which is really crippling (e.g., its one of the reasons ghouls punch so far above their weight class by hit dice).

Note that no actual damage value is given -- I think this and the rust monster are the only two creatures to this point that lack a damage value or some other clear way of killing a PC (i.e., by poison or other death effect). This makes it a major trap and counterexample for any system that tries to measure monster threats by some kind of a-la-carte points system.

In our discussion last week, several opinions were put forward about what happens, as is quite likely, after a carrion crawler scores a TPP (total party paralysis). Does it just wander off, looking for actual dead meat (carrion), no-harm-no-foul? Does the DM start making wandering monster checks, who might actually kill the PCs and thus give the crawler something to scavenge (note that no duration was given to any paralysis abilities to this point). Does it presumably auto-consume the hapless PCs? Yes to all of these, depending what edition you play with.

AD&D Monster Manual (1977)

...

NO. OF ATTACKS: 8

DAMAGE/ATTACK: Paralysis

SPECIAL ATTACKS: As above

...

Carrion crawlers strongly resemble a cross between a giant green cutworm and a huge cephalopod. They are usually found only in subterranean areas. The carrion crawler is, as its name implies, a scavenger, but this does not preclude aggressive attacks upon living creatures, for that insures a constant supply of corpses upon which to feed or for deposit of eggs. The head of the monster is well protected, but its body is only armor class 7. A carrion crawler moves quite rapidly on its multiple legs despite its bulk, and a wall or ceiling is as easily traveled as a floor, for each of the beast's feet are equipped with sharp claws which hold it fast. The head is equipped with 8 tentacles which flail at prey; each 2' long tentacle exudes a gummy secretion which when fresh, will paralyze opponents (save versus paralyzation or it takes effect). As there are SO many tentacles with which to hit, and thus multiple chances of being paralyzed, these monsters are greatly feared.

A year later we have the 1E AD&D Monster Manual, which is almost entirely backwards-compatible with OD&D, and mostly just compiles all various stats for each monster (formerly spread around in separate pages of each book) in one place. It still gives no positive damage other than the paralysis effect, and no duration for that ability, either.

The text says that it's willing to attack living things, "for that insures a constant supply of corpses upon which to feed or for deposit of eggs". Without any specific mechanics, this could open up DM to interpret it in several ways. Maybe paralysis leads to death; maybe it waits for wandering monsters; maybe it injects eggs into PCs who get consumed by them immediately or later. The mind boggles at the hideous possibilities.

D&D Basic Rules (Holmes, 1978)

This scavenger is worm shaped, 9' long, 3 feet high at the head and moves quickly on multiple legs. It can move equally well on the wall or ceiling as on the level. The mouth parts are surrounded by eight tentacles, two feet long, which produce paralysis on touch (i.e. when a hit is made).

Holmes Basic is usually a faithful editorial presentation of the same rules as seen in OD&D. I briefly point out this book because it more explicitly gives a stat block for the carrion crawler that says, "Damage: 0". Zenopus Archives has a great series poring over the original Holmes manuscript for this book, which we know Gygax did an editorial pass on before publication. (And he makes the point that possibly one could argue in OD&D that by default every crawler tentacle gets a stock d6 damage on every hit, but that's taken off the table with this clarification.)

D&D Basic Rules (Moldvay, 1981)

This scavenger is worm-shaped, 9' long and 3' high with many legs. It can move equally well on a floor, wall, or ceiling like a spider. Its mouth is surrounded by 8 tentacles, each 2' long, which can paralyze on a successful hit unless a saving throw vs. Paralysis is made. Once paralyzed, a victim will be eaten (unless the carrion crawler is being attacked). The paralysis can be removed by a cure light wounds spell, but any spell so used will have no other effect. Without a spell, the paralysis will wear off in 2-8 turns.

As usual, Tom Moldvay makes the helpful decision to specify a duration for the paralysis for the first time. His stat block is back to saying, "Damage: Paralysis" (as opposed to 0 in Holmes). But most keenly he states that crawlers simply eat their paralyzed victims by fiat. (!) So DMs used to running the B/X or related systems likely have the intuition that crawlers just swallow their prey whole like a snake. No save for you.

This same ruling is carried forward later into the Mentzer BECMI set. The Alston Rules Cyclopedia is largely the same with tiny adjustments: the stat block there says, "Damage: Paralysis or 1 point", and the text sets a timer on fast one eats paralyzed bodies: they "will eat paralyzed victims in three turns".

AD&D Monster Cards (1982)

Carrion crawlers attack with 8 tentacles that secrete a gummy fluid that will paralyze any opponents hit for 2d6 turns unless they save vs. Paralyzation. Carrion crawlers wll continue to attack as long as any opponents are unparalyzed. They will kill paralyzed creatures with their bite (DM 1-2), in order to have a constant supply of bodies to eat and to lay eggs in.

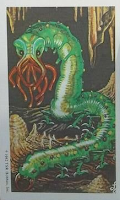

The AD&D Monster Cards are kind of a fascinating a beautiful set of products (the art at the top of this post is the front of the Carrion Crawler card). There are times I'm tempted to run a classic game by always showing players these cards, with name and info hidden on the back -- except there are too many gaps of key monsters that were never included (please, someone make a fill-in product here, take my money so I don't have to do it).

While the stat blocks are mostly identical to what's in the Monster Manual, these cards make some surprising, fundamental tweaks to certain monster rules. For example, you can see here that it specifies values for carrion crawler paralysis time (2d6 turns) and its capacity post-paralysis (a bite attack for a 1-2 damage). Other examples include specifying the duration for Ghoul paralysis for the first time in the game. So now the issue clarified for the AD&D line: a paralyzed party will clearly get TPK'd by the crawler.

This duration and damage was copied forward verbatim into 2E AD&D, for example. In 3E the duration was given as 2d6 minutes, and the post-paralysis bite damage was raised to 1d4+1.

Big thanks to our patron Adam for pointing out this detail to us.

Conclusions

At the outset, carrion crawlers have a fairly open-field ability profile that DMs could potentially fill in many different ways. But over time each of the bifurcating Basic and Advanced D&D lines of the 1980s-1990s came around to specifying a relatively limited paralysis duration, and a direct way for crawlers to finish off prey that they'd paralyzed -- including some small-damage bite attack in their final forms.

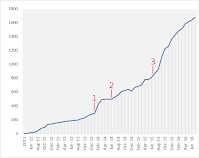

Even with that specific damage figure, their main disabling threat is of course the paralysis ability, so systems that try to mechanically crunch damage numbers will still trip up over evaluating these monsters. In the OED Monster Metrics simulator, a carrion crawler with its full 8 attacks gets assessed at EHD (equivalent hit dice) 12, while a reduced one with 4 attacks is still EHD 9. (Note that latter form is what I customarily run with, coincidentally similar to what Mentzer rationalizes in his games.)

How do you like your carrion crawlers? Are you happy with the post-Moldvay consensus that crawlers definitely terminate their paralyzed prey, or would you prefer different possibilities?