This is Part 3 of our exploration of different ability-generation methods in O/AD&D, and the chances for creating characters of different desired classes. The last installment was all about 1E AD&D according to the core books (PHB 1978 and DMG 1979). Today we'll be inspecting the Unearthed Arcana supplement that came out six years later (1985), the last year of Gary Gyax's tenure at TSR, as the initial D&D boom faded and the company was in dire need of a boost to income. As many AD&D players agree, that book overturned a bunch of apple carts.

Boilerplate reminder on ground rules: We're looking only at entry possibilities

for single-classed humans, not considering demi-humans with racial

adjustments, multi-class combinations, etc. Statistics were generated

from Monte Carlo-type simulations from my C++ program (and spot-hand-checked in a few cases and against other resources). You know the drill.

Ability Generation Methods

As an expansion on 1E AD&D, the Unearthed Arcana enhanced game obviously relies on the same stat-generation methods presented in the core rules. Recall the notable oddities there: (a) stat generation is not given in PHB, being locked away in the DM's book, (b) 3d6-in-order was disavowed as a generation method, and (c) the four methods that did appear were explicitly intended to make it easier for PCs to qualify for various classes of interest. You can see specifics on those 4 methods in the last post.

Even though Unearthed Arcana is just one volume, it's still split into separate sections for the player vs. the DM, with separate tables of contents, indexes for tables and charts, and everything. Presumably the player should not read the DM's section.

But if you do read that DM's section, you'll see that it starts with a proposal for a new Method 5 for ability score generation. They key point of this method is this: It guarantees access to any class that the player desires. ("subject to DM's approval", of course).

Specifically: The player chooses a class for their human character -- the rule explicitly says it can only be used for humans, thereby, I think, dodging the complications from multi-classing for the same reason we do in these articles. The DM gives consent, then turns to a table that specifies how many dice to roll for each ability score. For example, a Paladin will roll 3d6 for Dexterity, 7d6 for Strength, and 9d6 for Charisma (the maximum in the table). In each case you keep the best 3 dice for your ability -- and if you still don't have the minimum for the class, then it's automatically mulliganed up to that minimum. Pretty neat.

Two things about this new method occur to me. One is that Gygax here, precisely at the moment his official leadership of the game ends, completes a journey from OD&D being extremely strict about player entry to subclasses (e.g., less than a 2% chance to qualify for a Paladin initially), to making more-generous-allowances with the methods in AD&D (e.g., 24% to get a Paladin with Method 1), to completely expunging the randomness of that choice, and letting players take any class by fiat. That's obviously been the idiom of the game in later years, and was likely inevitable -- but there's at least a little tension in that generosity, which at the same time makes formerly-exotic options somewhat less special, and less worthy of the frenzied celebrations we once enjoyed.

The second thing is that, of course, Method 5 short-circuits the whole point of this series -- to analyze the chances of qualifying for various classes in O/AD&D with the different methods available. Using Method 5 the answer to that is, of course, 100% in every case ("subject to DM's approval"), and it basically time-stamps the moment when the whole topic became merely an academic issue. So I actually won't consider it further, and assume you're still only using one of Methods 1 to 4 for your AD&D character generation.

Classes and Requirements

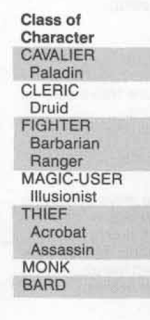

What we do need to analyze are the additions and changes to the various character classes in Unearthed Arcana. While Method 5 is pretty clearly an optional variant (it's in the DM's section, it's one more in an array of method possibilities), the character class changes are all in the front-facing Player's section, and are presented in a way that they look like core changes for the play of AD&D (assuming you use Unearthed Arcana at all, obviously). Some of these are frankly hard to look at. Here's how the list of AD&D classes is now presented in Unearthed Arcana:

So the first thing that jumps out is that whereas since 1975 we've had 4 primary classes (fighter, magic-user, cleric, thief) with their various subclasses, here Gygax brazenly sets forth the "Cavalier" as a new 5th primary class, and moves the Paladin subclass from the Fighter branch to Cavalier, with several class modifications flowing downstream as a result. Ugh. Gygax writes (p. 16):

The paladin is no longer considered to be a sub-class of the fighter, but is a sub-class of the cavalier. A paladin must have all the requisite ability scores of the cavalier, plus a wisdom score of at least 13 and a charisma of 17 or higher...

Now, the Cavalier's own stiff ability requirements are: Strength 15, Dexterity 15, Constitution 15, Intelligence 10, Wisdom 10 (resembling the Monk requirements quite a bit, actually; the only thing they don't have an explicit requirement for is Charisma). And then you combine this with the other Paladin requirements (Charisma foremost of all), and you see the Paladin now needs: Str 15, Int 10, Wis 13, Dex 15, Con 15, Cha 17. Yikes!

In addition to that, of course, Gygax has also added the new classes of Barbarian and Acrobat. Being held out as super-special options to spice up the AD&D game (and book sales), they too have very high ability requirements. The Barbarian (largely based on Gygax's earlier writeup of Conan for AD&D in Dragon #36) needs Str 15, Con 15, and Dex 14. They also uniquely have a maximum on Wisdom, in that it can't be over 16 -- which I've ignored here, as it wont make any visible different in the acceptance statistics. The Acrobat needs Str 15 and Dex 16. Note they're presented as a "split-class" (another early iteration on the "prestige-class" idea, like the Bard), in that you have to start as a normal Thief and then switch into the class after reaching 5th level. All of these new classes will be very hard to qualify for via standard dice-rolling methods.

Here are the combined requirements for all of the AD&D classes as given in Unearthed Arcana:

Qualification Chances

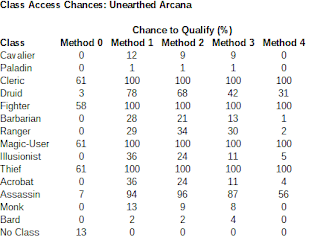

Presented below are the results of our simulator program to find qualification probabilities for the various methods and classes in Unearthed Arcana. Recall the "No Class" row at the bottom is for the case of a PC have more than one ability in the 3-5 range, and thereby barred from picking any class due to a fluke in the AD&D fine-print rules (although that's basically negligible for any of the official Methods 1 to 4). Classes are presented in the same order as the book:

Recall that the instances of 0's and 100's in the table are the result of rounding -- e.g., the 4 original primary classes are 99.8% to be available to any Method 1 character.

Note that the Cavalier doesn't look at all like those other primary classes, does it? The chances to qualify for a Cavalier are, as expected, very close to those of the Monk -- at one time the hardest-to-qualify-for class in the game. Both are about 12% likely by Method 1, about 9% by Methods 2 or 3, and about a third of a percent chance by Method 4.

The new Barbarians and Acrobats are at about the same tier as the earlier Rangers and Illusionists -- about one-chance-in-three to qualify with Method 1, and less for other methods.

But the standout result from Unearthed Arcana is that the Paladin (remember, it was the first-ever subclass introduced to D&D), with its sky-high stacking of various ability requirements, has once again returned to being the most extremely rare class in the game -- even harder to qualify for than the Appendix-quarantined Bard! It's approximately 0.9%, 1.0%, 0.8% likely by Methods 1, 2, and 3 (respectively), and less than 0.01% by Method 4. Rounding off, we can say it's pretty close to impossible to make a Paladin in 1E Unearthed Arcana -- unless you use the new Method 5, at which point you're guaranteed of your preference.

And that's where we'll end this series. It runs exactly parallel to the decade of Gary Gygax's direct involvement with the D&D game design, from 1974 to 1985. We've seen a progression from high rarity for subclasses from random ability generation, to open-access by player fiat, if you use the possibility of Method 5 generation mechanics. On the other hand, if you don't use that, we've seen the Paladin cycle from high-rarity to more-accepted, and back to maximal-rarity at the end.

What's you overall take on our compleat catalog? What bits and pieces would you actually want to use from Unearthed Arcana, if any? And what further topics should we discuss live at Wandering DMs?