That series had 3 parts, but was originally intended to have 4. The prior parts focused on:

- Diseases switching from real-world named contagions, to packages of complicated symptoms and affected body parts.

- Ship movement switching from per-round tactical tabletop scales and points-of-sail (and specific numbers of crewmen), to units of miles-per-hour and stripped-out wind directions (as well as hazy broad ranges for crew).

- Overland movement switching from specific hexes-per-day on a recommended campaign map scale (with a clear rule for handling changes in terrain), to a more generalized miles-per-day which are not evenly divisible by any possible map scale (and no rule for handling the obvious case of covering multiple types in a day).

Now, eight years later, I'm at long-last filling in that final 4th part. Sometimes I get hugely delayed on important tasks, but I do generally keep track of them. My coming back to this is partly inspired by the always-excellent Justin Alexander of The Alexandrian blog, who wrote a series of posts on Twitter last week defending the wandering monster mechanic, like so:

I like that a lot; well put, as usual, Justin. However, I'll add a bit of a nuance: Arguably Gygax fell down on precisely that issue in the 1E AD&D core materials; such that if a player first became familiar with the game through those books, they might actually have a reasonable criticism about that. Digging into specifics:

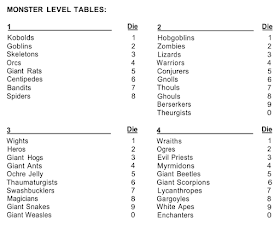

Original D&D, Vol-3, Underworld & Wilderness Adventure (1974)

Here we see the first 4 monster level tables (out of 6) for Underworld adventures. These tables are reasonably sized: either 8 or 10 monsters listed per level. My primary point is this: These tables are specific to the environment of Gary's Castle Greyhawk. It doesn't say that explicitly in the book, but if you compare the monsters on the Level 1 table to the first level key of Castle Greyhawk (unearthed and analyzed here earlier this year), you'll see that it's all precisely the same monsters. If they're on the wandering table, it's because they have a lair or nest on that level, and vice-versa. Every random encounter indeed gives a clue as to what the nearby lairs are about. And we know from other verbal sources that lairs and themes of other levels likewise matched the distribution of monsters on the other tables seen here. Every possible random encounters is a synthetic reflection and communication of the environment around you.

Advanced D&D, Dungeon Masters Guide (1979)

As the game expands and new monster listings expand between 1974 and 1979, Gary makes the mistake of expanding the wandering monster tables in the core rulebook to make sure that they include every monster in the game. Here are two (the Level I and Level VII lists):

That's, um... a lot of monsters. Frankly, way too many. (Instead of 8-12 types per table in OD&D Vol-3, we see 20-40+ listings in these tables, not counting the subtype tables). It's too many to build any cohesive theme or tone around, way too many to place lairs for all of them on the densest dungeon map I've ever seen. Every type and subtype of men, demons, devils, otyughs, and dragons (the types there likewise doubled from OD&D) are included.

The fundamental problem here is that the random monster tables have become disconnected from any specific adventuring environment, such as Castle Greyhawk. Rather, the tables' primary function has become an encyclopedic index to list every monster in the game (and also indicate their power level). Encountering a particular monster from these tables likely tells you nothing about the ecosystem around you; there's no reason to think an associated lair exists, and chances are basically negligible that you'll ever meet the same type a second time (so no preparation or strategic response will help you). If you were adventuring with these tables in use for wandering monsters, actually, yeah -- there would seem to be no rhyme nor reason to what was happening.

This is sort of a classic, even understandable, misstep which leads to design "bloat". You're only adding a few extra monsters at each step (e.g., OD&D Vol-3, then OD&D Supplement-I Greyhawk, followed by Supplement-III Eldritch Wizardry, then here in 1E AD&D DMG; each publication expanded the tables a little bit). What are you going to do today, paste in a few more monsters to your tables, or overhaul the entire system you've got going on? Most days and workplaces, the answer will be the former. Without tasteful editorial oversight, you get the "bloat" and loss of effective functionality.

Of course, that's just the story for the dungeon encounters; an identical story runs through the wilderness encounters. In OD&D Vol-3 they're pretty reasonable in size (like the dungeon tables, they take up just 2 digest-size pages in the book). In the AD&D DMG, every climactic zone and terrain type on Earth gets its own table with every imaginable animal and monster listed in them -- often a whole standard-size page is needed for a single table (the whole runs over 8 pages, not counting the tables for cities, castles, ethereal/astral planes, etc.) The table for Tropical areas alone has over 50 entries.

Furthermore, this bloat problem continued even further in the follow-up AD&D monster book of the Fiend Folio. Still committed to this same creaking design idiom, the authors were compelled to present all brand-new encounter tables for every dungeon level and wilderness area, again including every single monster in the entire further-expanded game. Now every single dungeon-level table requires a whole standard-sized page to fit it (e.g., the Level VII table has over 60 entries in it, plus follow-up dragon and sphinx subtables). Likewise the mammoth wilderness tables go for more and more pages. Over 15% of the whole book's page count is just the wandering monster tables, basically without any rhyme or reason. Just: Everything in the entire world, here in one place.

Advanced D&D, Monster Manual II (1983)

Now, I'll come back around and finish by giving Gygax some praise in the end: ultimately he did see the problem with this design path and made a course-correction in the Monster Manual II (this being a short 2 years before he departed TSR). Here, the new tables at the back of the book are, for the first time, cut down to a more manageable size.

The mechanic used in all the tables here is a somewhat oddball method of 1d8 + 1d12, such that a range of 2-20 is generated (19 monsters in every list), with a "flat spot of equal probability in the 9-13 range" (as he writes), and bell-like tapering of chances down at the extremes. As usual, tables are presented for every dungeon level (I to X), outdoor climate types, aquatic zones, etc. Many iconic monsters are left out entirely (note the weirdly exotic population in the tables above); and there are no subtype tables (other than for character parties). The whole system matrix, underworld and wilderness, takes only 6 pages in the book (admittedly in a very small font, and with no art).

More interesting is that following this is a section on, "Creating Your Own Random Encounter Tables" which explicates the mechanic and encourages the DM to make their own customized tables for specific adventure locations, as follows:

Two example are given: both wilderness tables ("Elven Forest", and "Spider Woods"), but clearly this system is meant to be used for customized dungeon areas, as well (otherwise, for example, no Giant other than the Hill variety can possibly appear in the game, etc., etc.). This is followed by 18 pages of teeny-tiny font listings of every monster indexed by every possible dungeon level, frequency class, climactic range, degree of civilization, etc. Clearly DMs are expected to pick from these (non-dice-indexed) master tables to populate their own d8 + d12 encounter tables. Finally, Gygax has written, "DMs are encouraged to tailor their encounters to their own worlds in a similar fashion".

With benefit of hindsight, is this a patently obvious thing for a DM to do? Perhaps. But it took almost the entire first decade of the game before anyone thought to write it in a rulebook. When someone picks up one of these big rulebooks, particularly as a child or teenager new to the game, one generally assumes that the structures defined in them give a reasonable play experience out-of-the-box. (If not, then exactly what are they for?) Even here, I'd opine that the d8 + d12 tables are too long at 19 monsters; as few as around seven things will likely fill up one's memory space (compare again to the OD&D tables at the top). So, I'd be happy with 2d6 or even 1d6 monster tables in my dungeons (compare to classic AD&D modules: the G1-3 and D1 series all have 1d3 or 1d4 tables; T1 and D2 have 1d6 and 1d8 tables; table size expands in later modules, etc.)

Even though Gygax finally saw the light and offered an explicit mechanic and advice for designing tables specific to a DMs' own campaign areas, I would argue -- at that point the damage had been done. Too many young people had picked up the books in the 1975-1983 era, used them as written by default, and had long series of wandering encounters that were confusing and disconnected from the adventuring environment they found themselves in. I think it's that play experience that gave random, wandering encounters a rotten smell that's lingered to this day. Anyway, that's my thesis: a whole lot of genius in those books, and also a large number of decadent semi-broken systems when Gygax tried to overly-abstract AD&D to make it the everything-game.

Phew! That was a bunch of stuff. I knew that was going to be a long one, which is why I've been trepidatious to write it lo, these many years. Big thanks to J. Alexander for kicking me back into action with a great observation on how wandering monsters definitely ought to be used, in synthesis with the immediate, specific adventuring locale.